The global tech industry is gearing up for a new world order that has an impact on Israel’s high-tech industry as well. What changed in the global economy in 2018, and what were the industrial trends during these past years in terms of funding, technology, and human capital?

The global tech industry is gearing up for a new world order that has an impact on Israel’s high-tech industry as well. What changed in the global economy of 2018, and what have this past years’ industrial trends been in terms of funding, technology, and human capital?

Tech industries today are more global than ever before. Capital, people, services and products are traversing borders at a dizzying rate, and tech giants have no less of an impact on citizens than national governments do. The Israeli high-tech sector, which operates within a small and open market, is particularly global by nature: most of its industry competitors and clients are scattered across the globe, it is highly involved with multinational companies and foreign investors, and it performs most of its transactions in foreign currency. This reality creates economies of scale, but it also makes it particularly vulnerable to changes in the global economy.

Recent years have been marked by global economic and technological trends that have worked in the Israeli high-tech sector’s favor: The global growth rate has increased, new tech markets have opened, and vast capital has continued to fuel innovative companies with accelerated growth. Accordingly, as of the publication date of this report, the performance of Israel’s high-tech sector in 2018 has been outstanding.1On the publication date of this report, final data on 2018 is not yet available. Therefore, data cited in the chapter indicates trends in the first three quarters of the year. Some of the diagrams provide an assessment of 2018 as a whole, based on the first three quarters of the year and on previous years

However, dramatic developments in the global economy in 2018 are reshuffling the deck – namely, the US’ retreat from the globalization trend, and the tightened regulations on the tech companies’ activities in developed countries. The global tech industry is laying the groundwork for a new world order which has yet to stabilize and its future impact on the Israeli high-tech sector remains unclear.

In this chapter, we will analyze key developments in the global and local high-tech sector over the course of the past year. In the first section, we will describe changes in the global economy in 2018 that are slated to be gamechangers for the Israeli high-tech sector, and we will review their ramifications. We will then examine key trends in the Israeli sector over the past year in terms of economy, funding, technology, and human capital.

Digital borders in a global world The rules of the game are changing

In the past two decades, the rapid penetration of digital technologies has been gradually creating a parallel borderless world. In this world, fast communication between people situated on opposite sides of the globe is now taken for granted. Consumers can benefit from products and services offered by countries that have no physical presence in their country, and development teams of different countries can work together and concurrently on innovative digital products.

Lately, however, governments worldwide have been reminding the global high-tech sector that it still operates on a country-by-country basis. Countries have begun to clash with tech companies and with one another over their share of the digital world’s taxation pie. This trend is upending the balance in the global tech industry. While it could potentially lead to improved equilibrium in the future, it is giving rise in the meantime to a great deal of uncertainty.

In 2016, the OECD released BEPS guidelines to address the floating profits of data-rich companies to tax shelters around the world, and encouraged the registration of intellectual property in the same country where it is being developed. By releasing these guidelines, the OECD aspired for tax harmonization that would guarantee the taxation of real economic activity in the location where value is created. Indeed, over the course of 2017, many countries, including Israel, began setting the groundwork for adopting these guidelines, and worked on updating their tax environment in order to appear more attractive to tech companies.

In 2018, however, Trump’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reform significantly transformed the existing structure. The reform includes far-reaching changes to the US taxation system that are designed, among other objectives, to draw economic activity of multinational US companies, including tech companies, back to the US. The most notable measures enacted with these companies involve a dramatic corporate tax cut and the issuing of GILTI and BEAT taxes.2BEAT (Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax) is a tax primarily applied to certain intercompany transactions issued to related foreign parties charged as an expense and deductible in the US, and to additional payments that are not included in the acquisition cost in the American company’s records. GILTI (Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income) is a 10% tax on supernormal profits of CFCs (Controlled Foreign Corporations) where companies can receive a credit on up to 80% of foreign income

These are slated to boost the tax liabilities of international companies that have reciprocal ties with the US such as companies operating in the US, companies owned by US residents, and companies that own US-affiliated companies.

The impact of these changes on Israeli high-tech companies is expected to be significant, because these companies are global in nature and have close ties with the US. The Israeli government recognizes the need to update its tax environment in order to remain attractive for both startups and large companies, and the government is examining ways to relieve their tax burden anticipated from this reform.

While tech companies across the globe are examining where to position themselves in order to benefit from optimal taxation conditions, another earthquake was caused this year by the OECD3OECD. (2018). Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalization when it announced that economic value from digital activity is not only determined by the location of a company’s core activity (such as R&D), it is also determined by the location where digital information is created, meaning the location where users are situated. Tech companies around the world are slated to be affected by this approach: companies operating in one country while providing digital services to users located in another country, as well as companies that gather digital information by use of a product or a service in order to generate revenue.4Ibid

The OECD has yet to establish clear guidelines for the implementation of this approach, but the European Commission has been quick to adopt it. As a temporary solution, it has proposed the imposition of a direct tax on revenue generated from digital activity where users or clients play a key role in creating value (DST – Digital Service Tax).5According to the European Commission, revenue subject to DST includes revenue generated from online advertising, revenue generated from digital mediation, and revenue generated from the sale of users’ digital information. The tax would be imposed on companies with an annual revenue of over €750 million with annual taxable revenue of over €50 million (Source: European Parliamentary Research Service, 2018) Those hit hardest by this tax would be large multinational companies – primarily US companies.

Since this proposal, if adopted, would apply to all EU member states, the tech giants’ contention over a piece of the tech giants’ tax pie is increasingly shifting from an argument between tech giants and European countries, to an argument between the US and European countries. Thus far, in the spirit of the EU proposal, England has already announced that it would levy a 2% DST on revenue generated from the digital activity of British users, and Hungary and Italy have announced that they would impose similar taxes as well.

The Israeli Tax Authority has also adopted the OECD’s approach to taxing revenue based on local digital users. The authority’s circular on “the taxation of foreign corporate activity via the internet”6Israeli Tax Authority, 2016(published in 2016) states the transformations evolving in the digital economic environment, and details incidences wherein services that multinational companies provide to users via the internet will be subject to taxation in Israel.

Alongside these developments on taxation, the trade war between the US and China that began in 2018 is an expression of government reaction to tech globalization, adding to a sense of unease in the global tech industry. In the context of US claims against Chinese practices on global trade, particularly on intellectual property and technology, over the course of 2018, the US imposed tariffs on a total of $250 billion dollars on goods imported from China, including tech products.7Hanemann, T. (2018, June 19). Arrested Development: Chinese FDI in the US in 1H 2018. Rhodium Group China, of course, retaliated by imposing tariffs on US products, with Chinese investments in the US dropping by roughly 90% in the first half of 2018 in comparison to the first half of 2017, reaching its lowest rate of investment in the past seven years.8For comprehensive methodology of the high-tech index for 2017: Israel Innovation Authority website

The upheaval in trade relations between these two tech superpowers could potentially upend the tech world as a whole. While many are expressing concerns, it could also create business opportunities for smaller countries like Israel, whose impact on the global order is minimal. Indeed, in light of the close ties that the Israeli industry has with the US market, and in light of the strengthening of ties between Israeli and Chinese innovation systems, Israel is following these developments closely as well.

Israeli high-tech in 2017-2018 – Decline in early stages and a boost in growth stages

The developments described are projected to make their mark on the global tech industry and on Israel’s high-tech sector in the near future. As of late 2018, however, players in the network of Israeli innovation who might be impacted by these developments – especially multinational companies, early-stage startups, and growing startups – are still on the fence and contemplating their next move. In the meantime, the Israeli ecosystem is continuing to flourish, and the trend of maturation and stabilization that we have been reporting on in recent years is continuing to intensify.

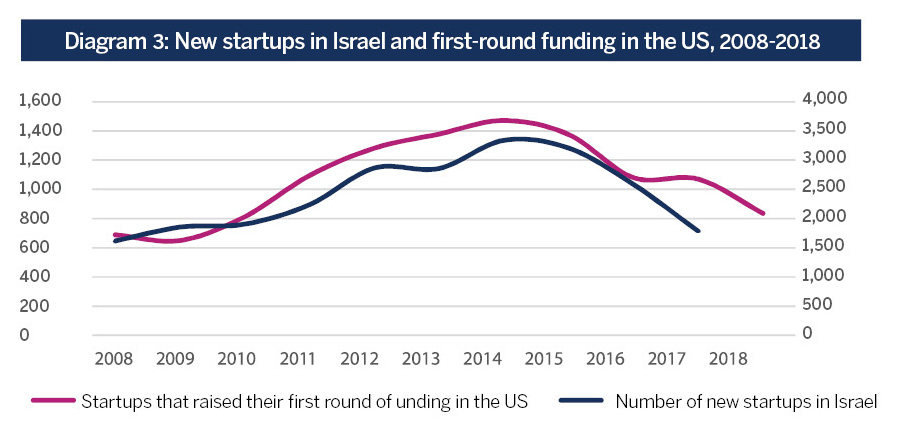

This account can be seen in the 2017 high-tech index and in interim data on 2018, as will be illustrated in this chapter. The high-tech index (see diagram 1), a synthetic index created by the Strategy and Economy Division of the Innovation Authority, is comprised of two sub- indices that depict the position of two distinct groups – startup companies, and mature companies.9 The index points to excellent performance in the two groups for 2017, but in the startup group, performance is lower than its peak in 2015.

Diagram by the Innovation Authority (see appendix)

the established companies’ group, the growth trend in 2017 is attributed to macroeconomic indicators: high-tech exports, high-tech output, and the number of people employed in high-tech. In particular, the total volume of high-tech exports grew by 8%. It is important to note that software9Branch 62 in the Central Bureau of Statistics’ 2011 classification of economic activities – coding and consulting on computers and other services, including the activity of startups, mature companies, and multinational software companies’ R&D centers is the main driving force behind the growth in all these indices.

Against the backdrop of the high-tech sector’s 2018 performance forecast lie this year’s shakeups in Teva. According to interim data, drug exports plummeted by 21% in the first half of 2018 in comparison to the same period in 2017.10Manufacturing Exports by Technological Intensity, September 2018, Central Bureau of Statistics,11The Israel Export Institute. (2018). Developments and Trends in Israeli Exports, first half of 2018 summary report,12It is important to note that manufacturing high-tech exports are marked by high centralization. Activities of Teva, Intel and other companies lead to acute changes in scope At the same time, in the first half of 2018, exports of R&D and software saw an uptick of 22% in comparison to the same period in 2017, and the export of electronic components grew by 55%. As a result, 2018 is projected to end with a positive trend despite the Teva crisis.13This is also indicated in industrial manufacturing indices by the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics

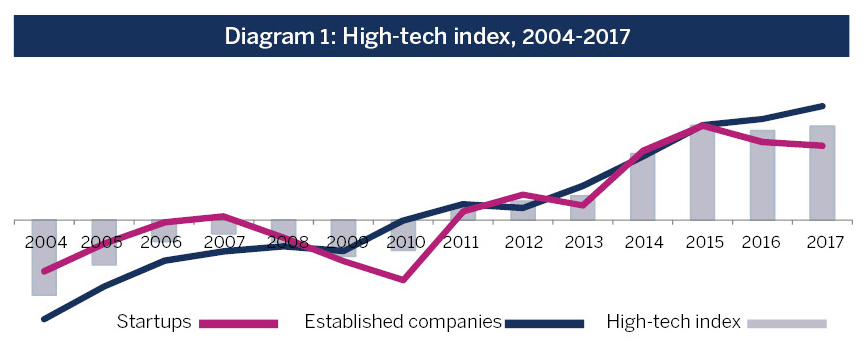

In the startup companies’ group, consistent growth in the volume of investments has continued through 2018 as well, with the total capital raised reaching $6.4 billion compared to $5.3 billion last year.14IVC and ZAG-S&WMost of the increase in capital raised in the past few years is attributed to growth companies (see diagram 2). Furthermore, 75% of the total growth in the volume of capital raised in Israel in 2012-2017 was from funding rounds valued at over $20 million. This data reflects the Israeli ecosystem’s trend of maturation, which we have been reporting on in recent years. In contrast, there is an evident decline in early stages. After a few years during which over 1,000 new startups were launched every year, 770 startups were launched in 2017, with preliminary data pointing to a further decline in 2018. Likewise, there is a downturn in the number of exits and in their total monetary value in comparison to the 2015 peak.

Diagram by the Innovation Authority based on IVC data15According to final data on 2013-2017 and a forecast for 2018 based on final data for q1-q3, and on q4 data from 2016-2017

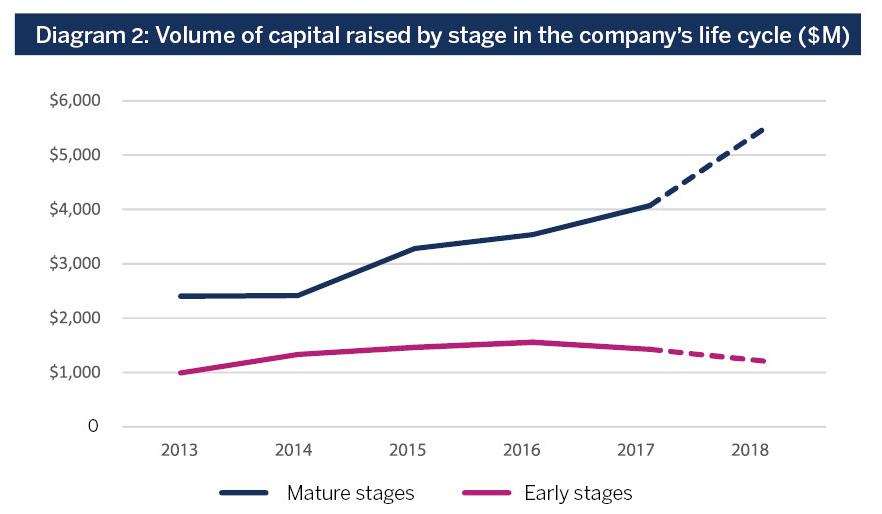

The overall picture in the startups group reflects global funding trends that are not sparing Israel. At the outset of the decade, economies across the globe were beginning to recover from the economic crisis of 2008. Investors were seeking high returns in an environment with low interest rates, and there was an accelerated flow of capital towards young startups around the world. In this climate, many entrepreneurs who were just starting out were able to raise funds with ease. In recent years, however, this has begun to change. Today, venture capital funds around the world prefer to gamble on a smaller number of promising startups and to ‘fuel’ them over a longer stretch of time with generous funding in the hope of eventually profiting from a huge exit, even if the wait is long. This is evidenced in the fact that the number of first rounds of startups in the US plummeted by over 40% in 2014-2018,16Pitchbook. (2018, October 8). The 3Q 2018 PitchBook-NVCA Venture Monitor. Pitchbook and a forecast of q4 of 2018 while the volume of capital invested in startups is steadily increasing – especially in growth stages. Furthermore, the number of huge rounds – raising over $100 million – has seen a significant spike in recent years.17Ibid

This climate has been fertile ground for the flourishing of unicorns – startups valued at over $1 billion that have not yet issued IPOs (Initial Public Offerings). Fifteen companies established by Israeli entrepreneurs are members of this club. In 2017, many people in the tech world viewed huge investments in unicorns with suspicion. Valuations seemed inflated, and it appeared as if investors would not be able to make profitable exits. nonetheless, developments in 2018 did not corroborate these concerns. The number of exits by unicorns grew – especially IPOs that offered investors impressive returns.18Glasner, J. (2018). Global unicorn exits hit multi-year high in 2018. As a rule, this past year has been marked by an uptick in stock value after two relatively slow years – a trend that has led to IPOs by companies that have already demonstrated significant growth and have surpassed early stages As of 2018, some believe that the preference of venture capital funds to invest larger sums of money in a smaller number of companies and to facilitate their growth is a new balance, and not merely a passing trend.

Israel’s high-tech sector is closely influenced by global trends; as such, the global processes described are closely correlated with processes occurring in the Israeli ecosystem. Diagram 3 illustrates the changes in the rate of startup launches in Israel correlate with changes in the availability of capital for early stages around the world. In other words, the drop in the rate of new startup launches in Israel reflects the global shift in investors’ preferences.

Diagram by the Innovation Authority based on IVC and Pitchfork data

In recent years, investors have begun to invest larger sums of money in Israeli high-tech for longer stretches of time and in a smaller number of startups. Accordingly, the number of capital raising rounds in Israel has been steadily declining, especially in early stages, while the size of the median round has been increasing. For example, the median raising of capital in round B was approximately $10 million in 2015 in contrast to $20 million in the second half of 2018.19Start-Up Nation Central. (2018). Israeli High-Tech H1 2018 Report

These trends mean that investors in Israel and across the globe are ‘choosing winners’ at a very early stage, and that the funding environment for early-stage startups is becoming highly competitive. In contrast, promising startup companies are able to raise private equity at an enormous scope and to grow rapidly without adhering to stringent conditions that public equity would need to satisfy.

Shortage in human resources – A change on the horizon

light of the funding trends described, in recent years, many Israeli companies have been on the path to rapid growth, fueled by large equity. Under these circumstances, they are required to recruit skilled personnel at an accelerated rate, and they are competing for these resources with other players in the ecosystem, especially multinational companies that are continuing to expand their operations in Israel.

Indeed, the tremendous demand for skilled developers and engineers is still being felt in the industry. According to a study conducted by Start-Up nation Central in collaboration with the Innovation Authority and Zviran, there were an estimated 15,000 positions available in the industry in 2018. Likewise, the rate of terminated employees in the sector has been steadily declining in recent years, while the rate of voluntary departures is increasing – a trend pointing to a high demand for human resources.20Startup Nation Central (2018). Human Capital Report 2018

The Israeli government is coordinating efforts to expand the supply of personnel skilled in all high-tech fields by increasing the number of students pursuing high-tech related disciplines in universities, by establishing a variety of extra-academic paths into the industry, by opening channels to recruit skilled personnel from overseas, and by encouraging the study of math and science in schools. In the context of these efforts, heavy emphasis is being placed on integrating women and underrepresented populations in high-tech (Arabs and Haredis in particular), with a recognition of the notable unfulfilled potential in these groups.

The results of the government endeavor can already be seen on the ground. On the academic front, the number of students studying engineering and computer science comprised 26% of the student body pursuing bachelor’s degrees in 2017-2018, demonstrating a significant spike in this field.22 Of this group, there has been a significant increase in the number of Arabs, who make up about 10% of the student body.23 In the extra-academic sector, this year saw a marked increase in elite training for high-tech professions due to – among other reasons – the Authority launching coding boot camps.24 Furthermore, with the objective of increasing resources by attracting overseas talent, the government created a Green Track for foreign high-tech professionals. The track expedites the visa applications process, in addition to ongoing efforts to help returning residents reintegrate into the Israeli ecosystem. At the same time, this year, the Ministry of Education reported that within three years, the number of students pursuing five points level in math doubled – a change that will begin to make its mark on the high-tech sector in a few years.

A field that has seen markedly higher demand for skilled human capital, especially recently, is data science. The rapid growth in the field of AI in the high-tech sector, as well as accelerated digitization in other fields such as the health industry, are creating an increasing need for skilled professionals. The worldwide demand for data scientists grew by 650% in 2012-2017,21LinkedIn. (2017, December 7). LinkedIn’s Emerging Jobs Report and it pays particularly well. In Israel, the average salary for a data scientist with five years of experience is nIS 27-32 thousand a month, the highest among many other development positions with a similar level of experience.22Ethosia data

Data scientists are required to possess an unusual set of traits: on the one hand, they need advanced capabilities in statistics and coding, and a familiarity with machine learning; on the other hand, they must be able to effectively and coherently communicate conclusions that arise from the sea of data, to provide solutions for business-related problems, and to play an active role in designing technological solutions. The demand for this unique amalgamation of traits along with the widespread requisite of a master’s degree or a doctorate (40% of positions stipulate this level of education) translate into a high requirement-bar creating a challenge to meet the growing demand at the necessary pace. Some believe that as the field continues to mature, especially as the rate of automation of data processing accelerates, threshold requirements for positions will drop.

Since the profession is still relatively new, there are still no targeted training programs for data scientists. Thus far, positions have been filled by people with an academic education in computer science, mathematics, statistics, and economics. Israel’s higher education system, however, has recognized the need for targeted training, and is quick to respond. Several universities such as the Technion, Ben-Gurion University, the Hebrew University, Bar-Ilan University, and the University of Haifa are now offering data science programs sponsored by the Planning and Budgeting Committee. At the same time, intensive boot camp-style career reorientation programs in data science are being designed for scientists from a variety of disciplines in exact sciences. The Innovation Authority recognizes the shortage of data scientists as well, and in the coding boot camps it opened in 2018, three out of seven supported programs provide training in data science or machine learning.

Emerging tech trends

The growing demand for data scientists is a reflection of profound changes in the world of technology. On the one hand, ‘classic’ ICTs (Information and Communications Technology) are reaching saturation point; on the other hand, groundbreaking technologies such as AI and blockchain are maturing and evolving rapidly, and are expected to tighten their grip in the coming years. At the same time, accelerated digitization of all aspects of human activity is paving the way for the emergence of new high-tech fields such as digital health, smart transportation, precision agriculture, and Industry 4.0.

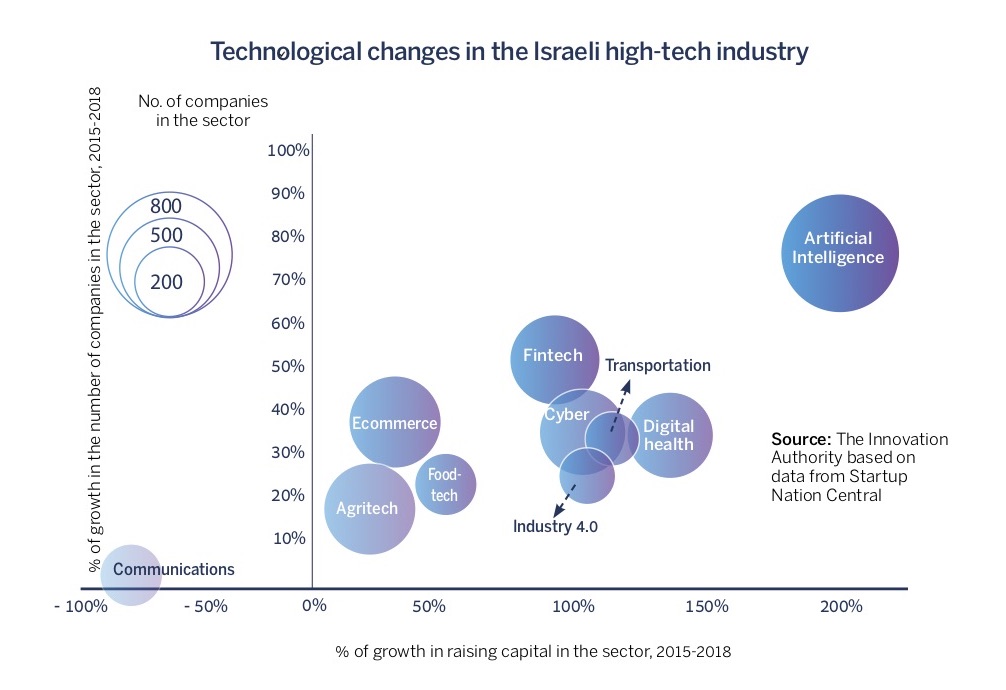

These trends are evident in the funding of global innovation. According to a report by Startup Genome, there has been a decline in investments in early stages and in the scope of exits for digital media, ad tech and gaming. In contrast, AI, blockchain ,robotics, and Industry 4.0 are growing rapidly.23Startup Genome. (2018). Global Startup Ecosystem Report 2018 Similar patterns can be found in Israel. Diagram 4 demonstrates that AI, digital health and transportation are leading in growth rate in terms of quantity of companies and the capital invested in them in 2015 and in 2018,24Data on 2018 refers to the first three quarters along with the more established fintech and cyber, which are continuing to show rapid growth. In contrast, the field of communications is showing significant decline.

Chiefly, the diagram points to the rapid growth of AI as the groundbreaking information technology of our generation – a trend we will discuss at length later in this report.25see chapter titled The Technology Power Race ItIt also points to the enormous potential of the Israeli industry in innovation applications of advanced information technologies. Transportation, for example, combines digital vision, big data, sensory systems, and communications. Over the years, Israel’s high-tech sector has excelled at leading implementation technologies; as such, its ability to produce innovative companies that are prominent in the field of transportation such as Mobileye and Innoviz is not surprising. Digital health is also based on a variety of advanced technological applications, and the national digital health plan launched this year is projected to propel it even further with a range of funding, infrastructural, and regulatory tools.26See chapter titled From a Startup Nation to a Smart Technological Marketplace

Blockchain – What does the future hold?

Distributed ledger technology (blockchain) has many potential uses; some are still far from commercial readiness, while others have already produced active marketplaces. Crypto tokens belong to the latter category, and can be divided into several types: tokens that can be used as payment, security tokens, and tokens for products and services. The field is currently known for its high volatility, but many people predict that once the technology matures and the hype dies down, the use of cryptocurrency will become a tangible reality.

2017, there appeared to be a new funding model for startups that was not contingent on traditional investors – decentralized funding by ICOs (Initial Coin Offerings). Some claimed that this funding method would replace venture capital as a funding source for blockchain companies; yet 2018 ended with mixed results. The plummeting value of various cryptocurrencies over the course of the year and the rapid collapse of many startups that had raised tens and hundreds of millions of dollars in ICOs in 2017 gave the field a dubious reputation, and public trading in cryptocurrency was halted. At the same time, the decentralized investment model was increasingly being based on venture capital funds and on other accredited investors, and less so on the general public.27PWC & Crypto Valley. (June 2018). Initial Coin Offerings – A Strategic Perspective,28Orcutt, M. (2018, July 3rd). Despite shadiness and crackdowns, the ICO boom is bigger than ever

In the meantime, regulators across the globe have been contemplating the legal status of these tokens and the necessary regulation, such as taxation concerns, the prohibition of money laundering, and the protection of investors. Regulatory clarity will allow the field to fulfill its economic potential and will keep speculators who tarnish its reputation at bay. In 2018, the Israel Tax Authority clarified its position on the taxation of cryptocurrency, and the Israel Securities Authority established a committee to examine the regulation of ICOs.

Corporate innovation in a world of disruption

The technological changes described – the widespread growth of AI and the rapid process of digitization in all segments of the economy, medicine, agriculture, energy, transportation and more – are blurring the distinction between high-tech and low-tech. In such a reality, corporations operating in all fields must prepare for swift changes in technology and business. Companies that are resistant to change will quickly discover that innovative and fast startups have become noteworthy competitors.

Large corporations around the world understand that they must take swift action in order to be part of the sphere of innovation and not miss out on emerging technologies. This phenomenon can be seen in a variety of ways. First, many corporations are investing in technological innovation within the company itself, as is the practice in large tech companies and in an increasing number of companies in traditional industries. Second, corporations in all fields are acquiring tech companies, a trend we reported on extensively in our 2017 innovation report. Third, corporations from all industries are joining the trend of open innovation and are collaborating with startups in a variety of models.

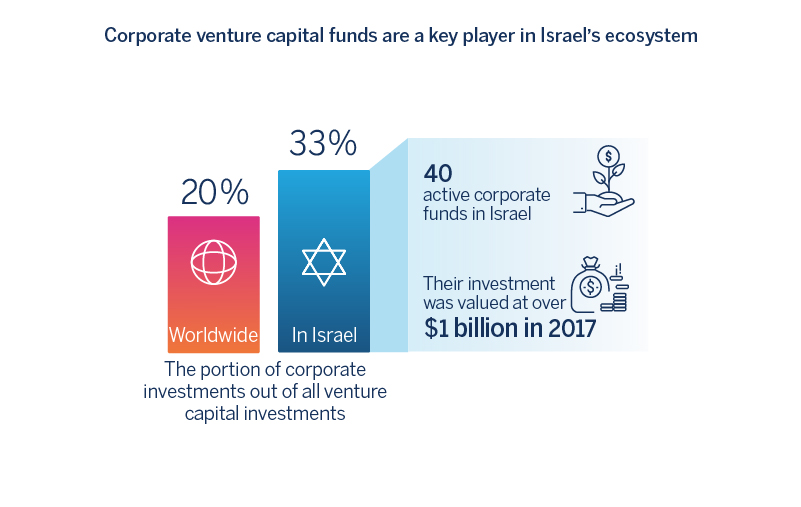

In the context of these trends, in recent years, corporate venture capital funds have become a more critical player – both in Israel and worldwide. In 2013-2017, the volume of corporate venture capital investments tripled, and they now make up approximately 20% of the total volume of venture capital investments worldwide.33 As for corporate investments, the demand for health, AI, and automotive technologies, the same technologies that we pointed to as being at the heart of startup activities in Israel and around the world, has become particularly prominent.

Corporate venture capital funds are especially prevalent in Israel. There are currently roughly forty funds of this type operating in Israel,29Startup Nation Central Finder including four out of five of the most active funds in the world. In 2017, their investments in Israel amounted to over $1 billion. Corporations amount to about a third30IVC Research Center. (October 2018). Israel Tech Funding Report, Q3 2018 of all venture capital investments in Israel, compared with 20% worldwide. This may be due to the massive presence of R&D centers Corporate venture capital funds are a key player in Israel’s ecosystem of multinational companies in Israel.

Collaborations with startup companies are critical to the assimilation of innovation in large corporations, but they do not guarantee success in their own right. A key challenge facing large corporations is how to integrate innovative ideas – either internal or external – and reach markets in an institutionalized, procedure-rich organizational culture. In a special interview for this report, Steve Blank, the world-renowned innovation expert credited with launching the Lean Startup Movement, shared his insight on the right ways for large corporations to invest in innovation in the 21st century.